Habitat : an

Examination of the Relationship Between Self Identity and the Possession and Display of

Household Goods.

The International Journal of Urban Labour and

Leisure, 2(1) <http://www.ijull.co.uk/vol2/1/000012.htm>

| Sophie Gibson | Habitat : an

Examination of the Relationship Between Self Identity and the Possession and Display of

Household Goods. |

Abstract.

This thesis seeks to investigate and analyse the theoretical and methodological problems associated with the sociology of consumption. In particular, there is a lack of clarity surrounding the ‘meaning’ of goods. A multiplicity of approaches have been used to assess this topic from disciplines such as, archaeology, social anthropology, economics, social history and more recently sociology. Whilst approaches have obviously varied between disciplines in accordance with their ‘concerns’ such as, producing a catalogue of objects of a past age, sociology itself has experienced diversities and ambiguities. Consumption for sociology has been approached from various theoretical positions, adopting different methodologies, touching upon wide-ranging topics. This article operates within a Material Culture framework, investigating one particular area of consumption: the meanings behind the consumption and display of household goods. This covers the importance of material culture: the relationship between people and objects. It explores how gender and age affect how we think about our homes. Throughout their lives, couples occupy a number of homes and the responses given here relate to which home they are currently occupying. This inquiry demonstrates how best to understand the ways in which individuals relate to their homes and possessions, revealing that there is a multiplicity of meanings about what the home ‘means’ to people.

Introduction and Background.

The term ‘consumer society’ is a complex one, but a general definition may be

established for the purpose of this debate. A modern consumer society can be recognised by

the motives that lay behind purchasing procedures. In contrast with traditional societies,

modern consumerism is associated with status identity. What are important are the symbolic

meanings and values that goods hold for consumers (Brewer and Porter 1993). To purchase a

product partly involves the consumption of images, including the consumption of lifestyle

images, rather than the purchase of basic needs. Emphasis is placed not on what is bought,

but the meanings associated with the purchased goods. What people buy and own is believed

to convey an impression about what sort of people they are and to reflect their lifestyle.

Consumption patterns have become indicative of status, in a similar way as job titles

(McCracken 1988).

Motives behind purchasing have undergone enormous changes, by becoming a route through

which to gain pleasure, satisfaction, status and prestige (McCracken 1988). Pleasure can

be derived from the dreams attached to goods, rather than the commodity itself. People

have become narcissistic; continually striving for more and the desire for further

satisfaction (McKendrick et al 1982). This process has filtered through society, but to

what degree and at what period in history depends upon the perspective one associates

with.

The non-durability of goods has increased, they are now bought to fulfill a specific

purpose for a limited time. Goods are often replaced before they are worn out or broken,

because people decide to buy the new, updated model. The shift in emphasis has been from

the utility of specific goods to their symbolic meanings (McCracken 1988). The factor of

increased leisure time has been used to argue that more people spend time shopping as a

result of reduced working hours (Hibbert 1987:599). It may be correct to state that more

people spend time shopping but too deterministic to state that shopping time has

increased. Williams (1982) pinpoints the introduction of credit as a vital feature of

modern consumption, along with the rise of the department store, which glamorised

purchasing through the display of goods in a more aesthetically appealing manner. This

contributes to the belief in increased availability of goods and new levels of browsing.

Mukerji (1983) in contrast, does not regard the rise of the department store as a crucial

feature marking the transition from pre - to modern - society, but all theorists accept it

as a distinctive component of modern consumer societies.

The majority of commentators point to the importance of advertising in stabilising (and

also increasing) consumption levels. Consumption has moved beyond describing a

products’ utility; goods are now imbued with symbolic meaning. Television

advertisements and billboards often limit the visual display of the product they are

selling with the result that the nature of adverts has become more abstract and

associative. Cultural principles find expression in every aspect of social life,

especially goods, enabling them to become both the creators and creations of the

culturally constant world. It is through advertising that consumer goods and the

culturally constant world are brought together. A combination of the above factors

constitutes contemporary consumer society, but each element is important to varying

degrees.

For example, Bourdieu's (1984) work explains how goods not only mark social differences,

but act as communicators. This relates back to work within social anthropology, where

writers such as Douglas and Isherwood (1980) first investigated social groups. They found

that whilst exchange is an important part of consumption, consumption involves

communication. They criticised traditional economic and historical writings for their

limited definitions of goods as merely fulfilling a subsistence need. Ultimately material

possessions carry social meanings (Douglas and Isherwood 1979:59). Bourdieu (1984) and

Veblen (1925) share one common assumption: taste is a key factor affecting the

significance of everyday goods (Miller 1987:147).

Bourdieu’s line of argument claims that the constant supply of new, desirable goods

is an important form of knowledge, displaying social and cultural values. He highlights

the new middle classes as a particularly important group of consumers who demonstrate the

importance of self-improvement through the appropriation of goods. Bourdieu’s

Distinction (1984) was the result of extensive empirical research in France. His work

breaks with the traditional line of structuralism, claiming that social action cannot be

reduced to a set of external structures. People are not just acting under rules, but on

the other hand they are not completely free individuals.1

For Bourdieu, social action is located between the two stances; the individual being

neither controlled by external forces, nor completely conscious of the full understanding

of social meaning (Lee 1993:31).

Advertising plays a part in determining a symbolic meaning. Whilst publicly held meanings

are significant determinants of meaning, they are not always conclusive. Goods are

markers, but their rapid circulation could suggest a threat of disorder, in terms of

clouding the readability of goods as signs of social status. Bourdieu however, denies this

is the case, as although goods and styles are copied, it is how one displays the good that

makes it an important marker and indication of status and identity. Those in the top

social groups veer towards high culture and those at the bottom are concerned with popular

culture, whereas those in the middle ‘aspire to legitimate culture, but lack cultural

capital’ (Smee 1997:325).

According to Featherstone (1991), social class distinctions are less formal and rigid.

Three new middle-class fractions2 have developed and issues of gender,

age, ethnic background and other cultural differentiation’s have increased in

importance. Classes are not disappearing as such, but more fractions are developing within

them, with their own dispositions.

What Bourdieu’s work has shown though, is that group membership does not precede

identity or vice versa, but rather that they exist simultaneously, but in potentially

different relationships. Thus, one cannot simply declare what it is to be middle-class,

young or old as each is inter-linked with an individual’s relation to self-identity.

In sum, ‘consumer culture provides an important context for the development of novel

relationships of individual self-assembly and group membership’ (Lury 1996:256).

Social Psychology

The most comprehensive study of the meaning of household goods was conducted by

Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberd-Halton (1981). This study was a quantitative investigation

into three-generation families in Chicago. This study is important for highlighting the

close relationship between personality and property (Formaneck 1994:329). They discovered

that objects incorporate the values and tastes of people and embody their accomplishments

in life. Objects represent links with others, such as family members and ties with past

ages and symbolise common links between partners by representing their lives together.

Objects help fulfil our sense of self, as they symbolise our personalities, status and

lifestyle, marking links with the past, present and future (Csikszentmihalyi 1981). Goods

have qualities beyond their functional use, ‘the things around us are inseparable

from who we are. Thus material objects we use are not just tools we can pick up and

discard at our convenience; they constitute the framework of experience that gives order

to otherwise shapeless selves’ (Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton 1981:16).

Dittmar (1992) too, argues that goods are laden with cultural meanings and images and

possess extensive symbolic significance for their owners and others. The acquisition of

goods expresses identity (Dittmar 1992:4). Material possessions therefore constitute a

language through which people communicate with one another. Goods reflect personal taste,

and mark differences between social groups, private and public space, male and female

space (Dittmar 1992:6). Material possessions are symbols of identity in personal and group

terms. Goods symbolise, ‘the personal qualities of individuals, [and] also the groups

they belong to and their social standing generally’ (Dittmar 1992:10-11). In the

modern world, ‘who we are has been defined more and more through what we have as

individuals: material possessions have become symbols of personal and social

identity’ (Dittmar 1992:13). Dittmar explains that the important issue is the nature

of this link and how individuals understand this connection. Socially shared

representations are not static as reality is context dependent. Meanings are acquired

through socialisation, in the form of education, the family and the media, but meanings

are constantly being reproduced and transformed. The messages that material symbols convey

‘are less overt and interpretation may not be conscious and deliberate. They ... may

have different meaning for different social or cultural groups, ...[and] material symbols

... reinforce status, wealth and power differentials. Material symbols allow for the

representation of social categories ...’ (Dittmar 1992:82-3). People do not passively

accept representations, but are socialised into understanding the meanings between

material possessions and identity. Thus, material possessions come to ‘symbolically

reflect self and others’ (Dittmar 1992:88).

Methods.

By using a number of data collection methods, the research project was given greater scope

and depth without incurring the need to resort to more costly and time consuming methods

(cf. Howard and Sharp 1983; Moore 1987).

Interviews

The particular form of interview ideal for this project was the semi-structured interview.

Whilst they are respondent-friendly, the reduced formality of semi-structured interviews

can allow the respondent to diverge from the relevant issues. This however, was kept to a

minimum. The respondents did go off on tangents, but they were not prompted to continue

along these lines.

The relatively small sample of this inquiry and the use of semi-structured interviews made

it problematic to generalise from the findings. This does not however, render the inquiry

futile. General themes can be drawn from the data and the information serves as a case

study for further research.

For the research study here, the sample focused on middle-income groups, who were

homeowners, with no (dependent) children. Whilst this may seem limiting in terms of

reflecting only one segment of the population, it allowed general themes specific to this

social group to be identified.

Gaining access to middle-class couples with no dependent children was a hurdle. To combat

this, the snowballing sampling technique was used. This sampling technique is particularly

useful when the population is difficult to find, as it introduces other potential

respondents to the project, through the recommendation of the respondents already

interviewed.

Snowballing does give a non-random sample, but bias was reduced by ‘breaking the

chain of contacts at the various points and restarting the snowball of informants’

(O’Connell Davidson and Layder 1994:177). The sampling chain was broken three times

to reduce the possibility of such bias.

Altogether twelve couples were interviewed. The interviews were conducted in the

respondents’ homes; men and women being interviewed separately. This enabled issues

relating to gender to emerge. Interviewees fell into particular age range categories: 20

to 30 year olds, 30 to 40 year olds, 40 to 55 year olds and 55 to 70 year olds. Each

couple comprised of individuals who fell within the same age range. From this focus, age

related responses became apparent. Three couples were chosen from each age range and for

all three of the 20 to 30 year olds, each were occupying their first bought home. The 30

to 40 year olds were all on their third of fourth home. Those in the 40 to 55 age group

felt that another move would be made, as did the 55 to 70 age group, except one couple who

inhabited the house intended for their retirement (Graph 1).

Graph 1 The number of homes owned in relation to age

| No. of homes owned | ||||

Last |

|

|||

5 |

|

|

||

4 |

|

|

||

3 |

|

|

||

2 |

||||

1 |

|

|||

Age range |

20-30 | 30-40 | 40-55 | 55-70 |

| Note: Last refers to

6-9 homes owned

|

||||

All the interviewees had no children living

with them. This was one of the criteria of the sample, because I wanted to gain

information about what the home meant to them as individuals and as a couple. Children

would have meant that time and money would have been redirected towards different goals

and desires, reflecting the needs and demands of the children.

Before the interview I telephoned each respondent to establish a convenient time for the

interview. I explained that it was important to conduct it within their own homes, to gain

detailed information. It was calculated that only one interview would be carried out per

day, to allow for travelling to their homes, recording observations, taking photographs,

and conducting the interviews.

Each interview took between 25 and 30 minutes and was taped. I assured them that only I

would listen to the tapes, and they would all be transcribed by me. On arrival I gave each

interviewee the opportunity to describe where in the home they wanted to be interviewed,

enabling them to feel more at ease for answering the questions. I was then taken on a

guided tour of the homes and asked if I could take photographs to illustrate some of their

responses. All were willing to oblige. I conducted 24 interviews overall, which proved

very time consuming. However, the data gathered was rich and detailed.

Prior to these interviews, e-mail interviews were conducted with the magazine editors.

Magazines undoubtedly, play an important role in creating and sustaining product images

and meaning. These email interviews were used to gain a perception of the issues that may

be important to this inquiry. In this respect, they were useful for generating theory and

formulating relevant topics for discussion with home-owners. The questions were aimed at

extrapolating general information about their readers and the aspirations of the

magazines. I obtained the sampling frame from a list of every interior magazine published

in the UK. I took every third name from the magazines that were published monthly. I felt

that conducting e-mail interviews would prove a novel way of conducting an interview, and

would perhaps elicit a greater response than by post. Although the number who actually

replied did not constitute a large sample base, they provided me with enough information

to draw general themes.

Visual analysis proved an important research tool for this project, photographic data

helped to illustrate this relationship because this inquiry was concerned with objects

(i.e. the visual), the meanings behind them and their acquisition. This research acted as

an illustration of the objects people cherished, rooms they loved and the overall interior

and exterior image of the home. In spite of this, photographic material has been absent

from most sociological research3

(Fyfe and Law 1988:2). Photographs provided evidence of the ways that people

related to their home environment, providing documentary evidence of a largely

unresearched relationship between people and household objects. In this project,

photographs were used as a supportive research tool, helping to assess and consequently

validate my research findings.

Results.

From the twelve semi-structured interviews with couples, general themes became apparent.

The most notable issue common to almost all of the interviews was the emphasis upon the

aesthetics of goods. The act of purchasing commodities partly for their aesthetic

qualities featured as a tremendously important part of peoples’ relationship with

their home environment. This special relationship altered in accordance with age and

gender. Where younger participants desired new and updated goods, older respondents found

pleasure in a wider range of goods, enjoying both contemporary and past goods. The home

was seen as a cherished part of peoples’ lives, personality and identity. It was not

seen as a finished entity, but rather as a reflection of peoples’ developing sense of

self and a marker of future aspirations.

Communication also surfaced as an important feature, in terms of goods communicating and

signifying qualities to the couples themselves, rather than to others. Whilst the outward

appearance of their homes was mentioned in terms of other peoples’ perceptions, the

interviewees stated that purchases were not bought as status symbols. I had anticipated

this response, but I felt this issue of status symbols may have been underplayed. However,

the most important issue was the pleasure homes gave to the couple themselves. The younger

respondents were concerned with the aesthetic appeal of their homes, but realised their

goals may be some way off. Pleasure was therefore linked with their short and long-term

aspirations.

Whilst general themes are identifiable, this does not suggest that all experienced the

same relationship with objects. From the responses given, purchases were both a reflection

of their social position, their personalities and lifestyles. This was particularly

evident when men and women who were part of the same couple gave completely different

answers to the same questions and focused on different objects and areas within the home.

While the younger couples showed the most marked differences, they were still able to

accurately guess the responses their spouses would give.

General Themes.

All except one of the 24 respondents thought that their home did reflect their

personality. Whilst asked how it did so, most took a few moments to gather their thoughts,

then gave a detailed response, drawing upon specific examples. Each person felt the home

should reflect their lives and personalities and acknowledge changes within their

lifetime. When asked whether and how the home reflected her personality, one replied,

[Laughs] ‘I hope it does. It reflects all our personalities. I think a home really

wants to be a reflection of your life and the things you enjoy doing and the various part

of your life and the present ... [there are] references to places we've been, houses we've

lived in ... and pursuits.’

For those respondents who lived in out of the ordinary buildings (12th Century church,

mill tower) the responses to this question were particularly detailed, their homes

reflecting the more ambitious side of the personalities. They realised there homes had

given them a life time opportunity and one which under other circumstances, if they had

children for example would have been inappropriate. Others reflected their passion for

beautiful things or their collections, feeling that either the inside or the outside (and

possibly both) of their homes were a great part of their identity.

Nineteen of the respondents, rated their homes as the most important factor reflecting

their lives and personalities, over and above their careers, cars and fashion. Four

respondents that made up two of the couples rated their homes and careers as equally

important and one rated the home second to their work. The following response sums up what

people felt about the home,

‘I don't think there's anything more important than the home. That sounds awfully

self satisfying doesn't it ... I see the home as one's sanctuary and it's very important

because we love it ....’.

The car on the other hand was not rated highly, many claiming it just got them from

‘A to B’. Whilst recognising that the home was not always a peaceful place, on

the whole people viewed the home as a haven, a place which one could decorate and organise

to please oneself, and retreat into from the ‘outside world’. Whilst some felt

their choice of building or colour of wall to be slightly misjudged, all spoke of a unique

feeling, a special relationship they had with their home. One respondent summarises this

point with the words,

‘Home is a sort of sanctuary isn't it ... I've always felt like that, even when I was

at home with my parents [some 50 years ago]. I remember [she speaks here of a past house]

I'd come back from work and I'd think, I'm back, I'm home ... I love going out, but I

think I'll go and then I'll get back.’ [a saying adopted from her aunt].

A final theme that struck me was the intensity of feelings for the aesthetic quality of

their homes. Whilst they knew that changes could make them feel happier, there was a

special relationship that already existed between each individual and a specific object,

or an area of the house or garden. One male respondent explained that their purchases were

made in terms of the beauty of the object,

‘We buy things because we like the look of them. When we see something we both like,

we buy it. It’s as simple as that.’

Their affiliation towards certain items did however, vary greatly according to age and

gender. Yet all highlighted some sort of bond, an emotional tie with an aspect of the

home. This however, is not to suggest that the home and its contents were irreplaceable.

Many highlighted their ability to be able to replace stolen items or recreate a theme if a

disaster occurred. So whilst their attachment to possessions was very great and they would

feel a sense of personal loss, many felt their health was the most important asset in

life. This was particularly reflected by the respondents over 45 years of age.

Most enjoyed their homes, referring to its beauty and spoke enthusiastically about it.

Motives behind purchases were quite straight-forward. If they ‘needed’ an item

for a functional purpose, its visual appearance was also an important factor. Those

objects without a practical function were bought as part of a collection, for general

interest or because they fitted in with the theme of a particular room. Both the utility

of the good and its visual qualities were important. Ultimately though, specific items

were bought for their visual beauty. When asked about the last item they had purchased for

the home, one respondent referring to a plate displayed as an ornament replied,

‘When I like something I buy it ... and I like what I consider to be pretty

furnishings and um, well, I just get great pleasure from buying things and seeing and

living in what I think are nice surroundings.’

This response seemed to sum up the importance of the aestheticisation of consumption, how

the display of the purchased good is an important aspect adding to the beauty of the

object itself.

When asked to describe their homes all the respondents began with a physical description.

This was interspersed to varying degrees with a visual description of specific items and

rooms. All respondents began with the age and design of the house and a description of the

number and types of rooms they had. Whilst this was somewhat expected, when asked to

describe the feeling and atmosphere of the home, many were initially unsure how they felt.

Overall the female respondents found this easier to answer. The home was either felt to be

calm and restful, or inviting, in spite of the clutter or untidiness. These responses were

important as they revealed that the home was more than a series of physical elements and

that above all they hoped their personalities would shine through, making it a welcoming

place to others. A male respondent said,

‘I think it’s a very welcoming and warm house, well that’s what we hope it

is to our guests.’

Other responses raised important issues related to age and gender.

Information obtained from the interviews was supplemented by another form of data

collection, namely observation. Guided tours around the homes were given by the

respondents. This enabled me to gather additional information and clarify points that had

already been given. The respondents pointed out objects and areas they had mentioned

during the course of the interviews. This form of data collection was verifies the

interview responses. The rest of this chapter will examine the themes that arose from the

interviews in accordance with the categories of age and gender.

AGE

Couples aged between 20 and 30 years

Both gender and age was relevant to many of the responses. Whilst older couples between 55

and 70 years shared similarities in their answers, the young couples exhibited obvious

differences, often giving conflicting responses. An important factor is discernible

in this. Spouses knew where their partner would differ and gave me accurate indications of

what they would say. When asked if this house was their dream home, the ideal they had had

in mind, a male respondent replied,

‘No, no, I would rather have lived in an older property, like one of the old cottages

on the main street in the village. My wife, on the other hand was angling towards a new

house to save on the amount of work and repairs. Yet, in the end, what with the problems

with the surveyors, it has all been a bit of a nightmare. X [his wife] will probably say

this is exactly what we were looking for, I know she will’.

His prediction was correct as his wife answered the question completely differently. This

highlights their varied tastes and aspirations for how they view themselves and their

desired lifestyle. His wife answered the same question with the words,

‘Yes, basically although we were looking for a two bedroom house, but we were shown

this one which has three bedrooms. Apart from that though, this is the picture we had in

mind. I bet X [her husband] has answered this question differently, as he wanted an older

house.’

For the women in this age group, the colour scheme of the home seemed very important.

Personal satisfaction with regards to their home was measured against this factor. This

often reflected the fact they has spent a long time considering this and had ultimately

had sole responsibility for the final decision. Their male partners were consulted, but it

was always the female’s ultimate decision. This factor is important as it shows how

happiness is equated with the beauty of the whole of the interior, rather than individual

items. Females did not feel a sense of satisfaction, until the whole of a room had been

‘finished’. When asked what objects or areas of the home they particularly

liked, the women of this age group always mentioned the walls of a room. This is summed up

by one female respondent with the words,

‘The most special place is my bedroom, which has everything matching. I spent a lot

of time choosing the right colours and design - it's a blue daisy print from

‘Next’.’

However, individual items did matter and if they were functional objects they still had to

be aesthetically pleasing to the eye. They used terms such as ‘making do’ and

‘putting up with’ certain colour schemes, fixtures and objects until they had

enough time and money to attend to them. They also seemed to know exactly what they were

going to replace these things with and how they wanted their home to look. One female

respondent explained that,

‘I like the house generally, as we painted it cream throughout, which makes it look

more spacious. There are many objects I don’t like, like some old chairs in the

sitting room, but I know what I’d like eventually. Until then, we thought it was

important to make the walls look nice. This was relatively cheap, so it was the first

thing that we did.’

Whilst both the men and the women knew that their homes would look better, given time and

money and possibly a different property, the male respondents were less bothered if their

present one looked a bit hectic and muddled. One man said,

‘It’s one step on from being a student house. It’s such a mishmash of

furniture; it’s just not co-ordinated. It feels like it’s a little bit untidy

... It’s just home, just a roof over our heads at the moment. It hasn’t really

got all the characteristics we want, things being planned and matched, but that will come

in time. It’s comfortable.’

This response was typical of the men in this age group. Whilst recognising that it was not

how they wanted it, they were content to live in it how it was for the foreseeable future.

The men were more inclined to not care if the house went ‘unfinished’ as it was

not their dream home. Their spouses on the other hand wanted to make the most of what they

had even though they were likely to move. The home was ultimately chosen because of its

simplicity, its functional attributes in terms of it needing little repair and being in a

good position for the motor way to reach work. Even so, their female partners saw the home

in a more visual and sentimental way. When the partner of the respondent above described

the sitting room she said,

‘It’s definitely home for me as its got all my bits and pieces in it. The lounge

is a bit seedy as its got videos everywhere. I reckon when people come and see it, people

our age, they like it, because its a similar style to what they have, but I think maybe

older people would find it quite sparse because of the way we’ve decorated it,

it’s very plain, no fancy wallpaper or fancy borders.’ (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Photograph of the above

respondents sitting room

Figure 1 Photograph of the above

respondents sitting room

Furthermore, this respondent had greater emotional investment in the home. This was

typical of the women in the age group. When describing the atmosphere of the house she

states that,

‘I have a sense of pride in it [pause] even though its X [her partner’s] name on

the mortgage, it’s our first home together that isn’t rented, its our first time

that we’ve been able to decorate and change things and so there’s a sense of

pride. It’s slow but things are looking as though they’ve got either me or X or

both of us imprinted on them. So it’s home.’

On the whole the female respondents saw the home as important reflections of their

personalities and whilst they recognised it may take some time to get it how they wanted

it, it was important to make the most of the available funds and live in relatively

attractive surroundings, until they could afford more ‘stylish’ pieces.

Whilst the male spouses of these women showed a greater interest in the home than expected

and had an affinity with the home, ultimately they saw it as a greater reflection of their

partner's likes and tastes. The newly wed male saw the home as the female domain, in terms

of creating a beautiful home environment. Whilst more than willing to give their opinions

on what they did not like, the three men found choosing fabrics and colours very tedious.

Whilst they had shown a greater initial interest, the choices were the female's final

decision. They would comment on their preferences for different things that they were

shown, but they did not actively seek out the choice of options. One respondent said that

the purchases for the household were joint decisions, but on further investigation he

admitted that,

‘I found the last lot of purchases so boring, so I let her [his wife] go out and come

back with the samples and then I said to her, ‘I like that’.’

Whilst both the twenty to thirty year old males and females recognised that the home would

eventually be a greater reflection of themselves, they still made choices based on visual

qualities. Whilst disliking some parts of their homes and particular objects, they were

very clear on how their home was going to look. Disliked objects usually belonging to the

spouse, which had be ‘let in’ against the other ones’ wishes and were often

put in a far corner of a room, out of the immediate gaze of visitors. This was not so much

that they were trying to show things that would symbolise their status or achievements,

but to hide the things one of other of them found to be particularly ‘ugly’. I

regard this as an inverted form of conspicuous consumption, because they attempt to

exclude objects that may not reflect their desired social status. One female respondent in

this age group was the only person in the whole sample to admit buying goods for their

culturally associated status. When asked whether she bought goods for their status symbol,

one replied,

‘Nothing major, nothing really expensive, but there’s lots of things I’ve

bought, nice things, purely because I know they’re going to look good on a table when

people come round [pause], like the glasses and crockery. Just little things, that not

only I’m impressed by, but I know other people are when they come round.’

Neither the men or the women were particularly interested in the garden or overly

concerned with the exterior of the building, except one couple who had bought their home

because it was a terraced house. This house was the couples’ second home and they

seemed to have taken a more informed decision about its external features than the other

two couples when they purchased it. This reflected the fact that they had previously lived

in a modern semi-detached house for five years and wanted the challenge of tastefully

bringing modern themes to a traditional property. Whilst the other two couples lived in

modern houses all of them showed a preference for older properties, but possibly at a

later stage in their lives.

All felt they had been influenced by magazines and what they had seen in their friends

houses. When asked where they drew their ideas from, magazines and other peoples’

home were cited. A female respondent said,

‘I think that magazines have influenced us quite subconsciously really, because I

don’t know where else I’ve got my ideas from. I’ve seen quite a few

magazines, because my sister gets Homes and Gardens. I’ve seen a lot of things I like

in there and this idea of cream throughout most of the house was definitely from somewhere

... I do like it, it’s not like I’ve just seen it and thought I’ll have

that. [Pause] It could also be an influence from my mum and dad’s home though, as

that’s cream’.

Her partner also recognised the impact of media images upon household choices, but felt

that they had not actually acted upon them yet. He explained that whilst he had collected

ideas form magazines and television programmes; he was keeping them in mind for the

future. Perhaps this was an underestimation of the subconscious influence of the media on

the choices he had already made. Whilst wanting stylish objects, all respondents wanted to

put their own personality onto their homes, in terms of the stylisation of these

fashionable goods. Whilst they cherished beautiful and contemporary items, they wanted to

display them in a slightly unusual fashion.

For this age group, the most special item or household feature varied dramatically, within

and between couples; most of the men stressed either practical objects (television and

video or electric shower) and women objects of visual beauty. Whilst one male respondent

said the television was the most special object, his partner said,

‘The most important thing is the bed [laughs] as it is an antique pine bed, the first

thing we ever bought ... it is my favourite piece of furniture and about the only

expensive thing we’ve got. I just know I’ll never go off it and it will follow

me everywhere.’

The second female respondent mentioned a set of tables she had been given by her mother as

a wedding gift, as they had great sentimental value. The male and female respondents of

the third couple stressed an area of visual beauty, but an area which had required

practical action from them. Both said the hallway, stairs and landing was the most

important feature of the home. This was because they had decorated it themselves and

fairly recently, having spent a lot of time choosing the right design. The wallpaper was

chosen as it was,

‘Contemporary with the date of the house, it’s William Morris’ ‘Willow

Bough’. It seemed an ideal choice for this sort of house. We liked the fluid nature

of the design, and its scale was right for the space.’

There is a direct association with a wider concern; the date and style of the house

(Victorian terrace). Its aesthetic beauty was intertwined with its marker as a

‘Victorian’ style pattern (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Wallpaper on the hall,

stairs and landing.

Figure 2 Wallpaper on the hall,

stairs and landing.

This couple was very similar to those in the next age range, most probably because it was

their second home. The homes of the younger couples had definite spaces that were

finished, areas that were developing and ones that needed attention. These issues were

very apparent, the couples viewing the home as a set of stages that needed ongoing

attention. Conspicuous consumption did not surface as a widespread phenomenon, but they

were obviously concerned with keeping the house very ordered, minimal and visually

pleasing. However, the scarcity of their possessions may be a factor of their lack of

economic funds, rather than an affinity with post-modern minimalist styles. They were far

from being showy or ostentatious, but they had definite ideas about what they wanted to

achieve and knew that these changes would give them immense satisfaction and positive

feelings about themselves.

All these couples were more openly interested in the interior of the house. The gardens

were either unattended or just a patch of grass. The inside was where they intended to

focus their interest, most notably in the fabrics and colours they used. The heart of the

home was either the bedroom or the sitting room, because it had been decorated by them and

they felt it was one of the ‘finished’ parts.

Middle-aged Couples - 30 to 40 year olds

The outlook of the couples aged between thirty and forty-five was slightly different. They

realised that since their twenties their dreams and tastes had changed and this was

reflected in their purchases for the home, their decoration of it and the type of property

they had bought. One couple had purposefully been looking to buy an older property, as

they felt that,

‘they have much more character and charm. We wanted a terraced house and one we could

do up ourselves. When we saw this house we knew it would be perfect. It hadn’t been

modernised, the old fittings remaining from the 1960s ... Its exterior was ideal, as it

looked pretty with the roses on it, and it hadn’t much garden, as we’re not into

gardening really. The plain interior enabled us to put our own tastes into it. Its been

gradual, and we’ve got a mixture of old and new styles, but we like it.’ (Figure

3)

Figure 3 Exterior of their home

Figure 3 Exterior of their home

This age range was more adventurous, using a mix of styles and objects, which were a

combination of pieces they had collected and been given. They were not preoccupied with

creating a common theme throughout, but tried to show that the home is a reflection of

their many and varied interests. Whilst they wanted a nice house, most enjoyed it because

of its clutter and contrasting ornaments. They were less idealistic in their outlook and

although they still had definite goals and felt the home to be a vital reflection of

themselves as individuals and as a couple, they realised home making was a long and

gradual process. One male respondent summed up his feelings about what the home meant to

him with the words,

‘I think the creation of the home is an ongoing process and a mixture of different

styles and tastes. My home does reflect my personality as I buy the things I like, which

is apparent with the type of things I buy and also in its design. Its visual appearance is

important, I think, for my own appreciation of it.’

The home signifies a joint unit, something that they purchased together. This was

particularly evident for the couple who were occupying their first bought home together.

Rented houses had been restrictive and been relatively ‘untouched’. They felt

this house gave them the opportunity to experiment with styles and be more creative,

making more effort to create a nice environment. One couple had lived in a rented house

together for two years before buying this current property. This purchase led them to have

a greater interest in the appearance of the home and felt it represented their

professional status and their personal identity and tastes. They stated that the most

important feature of the home was,

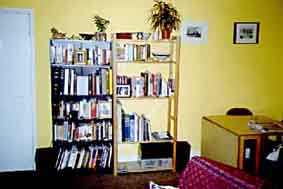

‘The space and privacy it gives us. Rented accommodation was somewhat cramped and

dreary and the most important objects to me are my books and ceramics.’ (Figure 4)

Figure 4 Picture of the sitting room

and their possessions.

Figure 4 Picture of the sitting room

and their possessions.

Both partners of this couple highlighted books as very special items. This reflected their

interest in reading and their enjoyment of visiting second-hand book shops. This age range

was very different from the others in terms of the items that were special to them. All

highlighted books, or crockery, and other items of relative insignificance to the eye of

an ‘outsider’. Their most treasured items were not showy, but very understated.

Other age groups highlighted objects with associations with the past or very ornate pieces

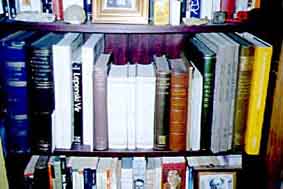

of furniture (Figure 5)

Figure 5 A picture of their

treasured items (books)

Figure 5 A picture of their

treasured items (books)

Four respondents4 highlighted

the equal importance of their careers as a reflection of their personality and status. One

said,

‘My job is extremely important to me as it is a significant part of my life and I

enjoy going to work, with the different challenges it gives me. The house is equally

important, allowing us to develop our interests. The home though, is a reflection of both

our personalities, where my career is important to me as an individual.’

This age range is less easy to group together as while two couples did not mention the

possibly of having children, one couple had actively decided not to have them. I felt this

fact was reflected in their answers, as their careers as well as their homes became a more

important part of the lives. Although none of the 12 couples had children living at home

at the time of the interviews, none of this age group had actually had children. The

couple who were not going to have children actively stated this was a reason why they

decided to purchase their home, as having children would have rendered the property

impractical. They had bought the home for its aesthetic quality and unusual properties.

The husband said that,

‘We didn't want to live in something ordinary. We liked it because it was different,

but suitable for people like us as we don't have or intend to have children. It wouldn't

be suitable for a family.’

This couple stressed the unique character of their home. This factor gave them immense

pleasure and satisfaction. Whilst both did highlight the importance of their careers,

their home an integral part of their identity and personality. Whilst they had not

specifically looked for an unique property, it was an immediate decision once they had

known it was available,

‘I had seen it before, but one Saturday afternoon we saw it in the estate agents

window after it had closed. By Monday, we knew we wanted it, just from the description of

it’

Although eager to personalise their home, they recognised it would be a gradual process.

They were concerned to improve the garden, as the interior did not require immediate

attention. The female respondent said,

‘We actually haven’t painted it, even though it hasn’t been done for about

ten years, as it fits in well with the stone and timber work. It’s off white and it

looks quite good. In another house you would mind ...’ (Figure 6)

Figure 6 The twelfth Century

Church’s Interior.

Figure 6 The twelfth Century

Church’s Interior.

From my observations those couples aged between 30 and 55 were the most creative

respondents in terms of their homes. Whilst they were also concerned to stress the

importance of their careers, from observing their homes it was apparent that the home

constituted an important part of their lives. It was after all their sanctuary from

outside pressures. Whilst some areas looked carefully planned, other looked like they had

evolved. They were not ordered homes or totally messy, but they reflected the different

concerns and interests of their owners. Many respondents felt the home to be a place where

one could be oneself. This was evident from the cosy and relaxing atmosphere of their

homes.

These two age ranges (30 to 40 and 40 to 55 years of age) seemed to show a greater

interest in the exterior design of the house, and felt that this was part of what their

homes meant to them. Their personalities were imbued in interior style of the homes, the

type of building it was and the garden. How these respondents used space was a very

important feature that I noticed, emphasis being placed of different areas for personal

comfort, and specific rooms for more formal occasions. This made their homes very

interesting to observe as some rooms looked in complete contrast with other ones. The

heart of the home for the 30 to 40 year olds was either the study or the sitting room, but

for the 40 to 55 year olds it was the living / kitchen area. Entertainment was one of

their keen interests, which was reflected in the warmth of these rooms.

Couples aged between 40 and 55 years

Those couples in this age range recognised the home as an important extension of their

lives. To them it was a reflection of the past and present and a symbol for their

future direction. They spoke of the memories imbedded within the home and with particular

objects. One female respondent described her home in a unique way, seeing it more of a

hobby. She explained that,

‘I think we’ve both had a lot of fun with the house and that’s we enjoy.

We’ve had a lot of fun decorating it ... what we don’t have time to do is play

with the house, move things around and so on. The house is basically a collection of our

past pursuits and our present tastes and interests.’

Another couple mirrored this theme, their home giving them the opportunity to do the

things they enjoy,

‘I love working in the garden and when we bought the property, there was no garden,

just tarmac. I’ve spent a lot of time building a pond and planting shrubs and plants

to get it exactly how I want it. It all takes time of course, but the garden is now

beginning to flourish ... Inside needed a lot of work, but we have enjoyed taking it back

to how it might have looked in Georgian times. We have obviously used modern materials and

have contemporary possessions, but I think it’s a good representation, which mixes

well with modern styles.’ (Figure 7)

Figure 7 Interior with mix of old

and new styles in a Georgian property.

Figure 7 Interior with mix of old

and new styles in a Georgian property.

The home is more than just a physical structure, as it represents peoples’ social

standing and tastes. It is a reflection of both their personalities and professional

status. When another male respondent was asked whether he felt that the home reflected his

personality, he replied,

‘Yes, I would have to say it does reflect our personalities, certainly in my

judgement. I like to think that what I’m associated with is quality. Quality in my

professional life and hopefully this comes through to quality in what we’ve done

here.’

This respondent felt that the most special feature was the hall with the mill tower,

because of its unusual qualities and professional workmanship. He said,

‘The hall is the most special area of the home to me ... it is unusual and the

lighting that we’ve had installed sets off the mill tower very well.’ (Figure 8)

Figure 8 Hall with mill tower

Figure 8 Hall with mill tower

The practical functions of the home were mentioned by two couples, both of which used the

home as a place of business. A male respondent explained the importance of the home in

terms of its housing his office space,

‘The rooms are all working for themselves. It is very much a working house ... we use

four of the rooms for the business ... It therefore reflects the different areas of our

lives and we have certain rooms for different occasions’.

The home therefore reflected both their public and private lives and incorporated their

loves and also what they felt to be their purchasing mistakes.

All the respondents in this group had vast houses. This however, was not the motive

behind the purchase. Each bought the property because they cherished its beauty, not

because of its' grand appearance. Two of the three couples tried to downplay its size, one

respondent saying,

‘Our first house was a little terraced house and to be honest, I liked that very much

indeed. I don't feel that I need a big house ... the main thing is just to be happy. It

wasn't that we wanted a large house, we just happened to get one’.

The respondents felt the most important thing was that they themselves gained pleasure and

enjoyment from their homes. Although all three couples in this age range were avid

collectors of antiques, they said that they enjoyed the activity of collecting and the

pleasure the objects gave them. Whilst none of them readily admitted to conspicuous

consumption, their wealth and status was apparent to my eye. I do feel however, that this

was a motivational factor in the purchase of their home, as their answers highlighted the

fact that they loved beautiful things, and that their own lives and health were ultimately

the most important things. One male said that if he had a fire in his home, he would,

‘Try and get X [his wife] out first and those living [pets] ... I can't think of

anything in particular I would go for. I'd have to say that at the end of the day I'm

insured.’

These respondents openly experienced great enjoyment from the visual beauty of their home,

both its exterior and interior. However, the general impression was that they would be

able to recreate this wonderful feeling in any house as they had imprinted their

personalities and tastes into previous homes. More importantly, one respondent said that

because his home was a splendid Georgian property he felt that although he put his and his

wife’s personality and mark onto the building, but he would never see the house as

‘his’,

‘... I don't feel that I'm the owner of the house and really I think we're good for

the house because we want to take it back to what is was. I look upon myself as more of a

caretaker and all I'm doing is looking after it until someone else can enjoy it.’

Thus, the home is not a factor determining peoples' personalities, but it constitutes a

type of hobby, like an interest in house restoration and helping in a small way to

preserve an historic buildings. People’s tastes and personalities help shape the

house. All three couples did however feel it important that their home reflected their

lifestyle and found a middle ground in terms of giving it a modern and cosy feeling,

whilst keeping the property in keeping with its' original intention. Thus, each of their

homes were a mixture of old and new objects, and an abundance of colours, textures, styles

and purposes.

Ultimately this age group gained immense satisfaction from their homes, by maintaining a

balance of preserving the old and adding their own tastes and preferences to make it a

more comfortable place to live.

Mature Couples aged between 55 and 70 years

Their responses were linked with their stage in the life cycle and their concerns about

their future health and the practicalities of the home. One of the three couples had

bought the property as their retirement home and the other two recognised they may have to

scale-down the size in years to come. The retired couple had bought this house for the

practical reason that they were getting older. It was a considerably smaller house than

their previous one and although they described it as somewhat ordinary from the outside,

their time of having splendid houses were in the past. Their concern were very much

focused on the ability to move about with relative ease.

Whilst the other two couples mentioned this fact, because they were at the lower end of

the age range it was not mentioned as much. Despite being interested in the layout and

manageability of the house and garden, the visual impact and comfort of the inside was

still very important. Each respondent had a special relationship with their home and no

matter how grand or mediocre it looked to others to them it gave them total enjoyment.

Surprisingly, there seemed very little gender variations for this age group. What struck

me was the similarities in the answers between partners and the three couples. When I

mentioned this former fact, I was told that after so many years together knowledge of each

others tastes was very well known. Furthermore, their ideas about what they wanted, what

they liked and what their homes meant to them were extremely similar. Their tastes had

developed and changed over the years, the home being a reflection and embodiment of their

lives and interests. Whilst they read interior magazines, any influences they had were

felt to be subconscious. They were not concerned with ‘keeping up with the

Joneses’, they just ‘liked what they liked’. One female respondent said

that she collected paintings, not for any other reason, but because,

‘I love them and want to live with them. I gain immense pleasure from looking at

them.’

To her, the home was a complete sanctuary, a representation of her total happiness. She

liked everything in the house, all her possessions, ornaments, collections and so on. Yet,

she was not too attached to anything in particular, valuing health above all else.

‘Oh, I feel at home everywhere in the house, absolutely. Yes, I think I like all

parts of it ... I like everywhere’ (Figure 9)

Figure 9 Sitting room with

paintings

Figure 9 Sitting room with

paintings

Admiration for the outside of the home was a common theme among this group. The garden was

an area that gave immense pleasure, whether one was sitting or working in it. It was a

less ordered area, where one could be creative. It allowed people to express themselves,

experimenting with ideas that were less timely and costly than experiments within the

house. One respondent described his garden in detail and the enjoyment it gave him,

‘I like it because its not too controlled, but a kind of ordered nature, but I would

like to make it a little more minimalist and suitable for advancing years [laughs], rather

than a cottage garden.’ (Figure 10)

Figure 10 The garden

Figure 10 The garden

Finally, all the couples over 40 years of age, and in particular those of 55 spoke of

their attachment to their ancestors furniture. They spoke of this furniture as if it still

partly belonged to their ancestors, feeling more as guardians of the objects. They

treasured these pieces because of their beauty and associations. They marked links with

the past, but they were not kept together as an historical area within the home, but were

mixed with modern styles and furnishings.

My first impressions were that the homes of the 55 to 70 year olds seemed much more

ordinary than the homes of the others. All of them seemed very plain looking buildings

with little out of the ordinary. However, once inside I was overwhelmed by the richness

and variety of their possessions, colours, fabrics and style. The outside had lulled me

into thinking they would be plain, uninviting homes, yet they reflected their passions and

tastes. If I had met the respondents elsewhere, I would not have been prepared for the

visual displays I found. For this group the heart of the home was everywhere. The home was

a complete entity and a place of much personal enjoyment and satisfaction. Most of the

rooms contained a mixture of furniture given by their ancestors, antiques they had

purchased themselves and modern possessions.

Summary

From the interviews, observations and photographic material, general themes began to

emerge. I discovered that the relationship between these people and their homes was not a

fixed one, but underwent changes and revisions. Furthermore, people expected different

things from their current property, than they had for previous houses and property they

expected to purchase in the future. The most notably factors affecting material culture in

this project, were age and gender. This is turn, influenced taste and aspirations. A

number of common themes arose throughout the research:

The home environment is a reflection of peoples’ personality, identity and status;

The aesthetic quality of goods is highly valued;

Goods involve a combination of instrumental and symbolic elements;

Symbolic attachments are not necessarily culturally shared meanings, but often relate to personal values;

Whilst the home is an important indicator of peoples’ lives and tastes, the home can always be reproduced, in the event of a disaster;

Associations with the home are linked to age and gender.

While not every respondent touched upon all

six of these points, most covered the majority of them. These themes are not

representative of all middle class people, but they are typical of my sample, who all

belonged to the central and upper divisions of the middle classes.

Discussion.

From this investigation, general themes and more specific patterns relating to age and

gender emerged. Whilst none of the theoretical arguments can be adopted entirely to my

findings, a number of points they raise are relevant. An examination of material culture

involved an inquiry into a complex relationship. As Campbell (1996) rightly warned, it is

limiting of social researchers to accept that culturally shared meanings associated with

goods, can be easily translated onto the meaning of actions. This is a problem associated

with both Veblen’s (1925) and Bourdieu’s (1984) work. In this sense a discussion

of objects does not necessarily lend itself to any inquiry of the motives behind consumer

purchases. Caution needs to be adopted.

My findings highlight that the appropriation of goods involves an complex relationship of

instrumental and symbolic elements, including culturally shared meanings and personal

attachments. However, I would not go as far as Dittmar (1992) to argue this is always the

case and that the combined elements constitute a stable balance. My research shows that

the consumption and display of goods involves a number of important issues outlined by the

various theoretical positions, but does not mirror any perspective completely. Contrary to

production-led arguments, my participants did not seem to portray passive consumers,

exploited by media images in their consumption purchases. Artificial needs were not

created and reinforced without their awareness, consumers being dupes of the Capitalist

mode of production. I found my respondents held a conscious understanding of the aims of

advertising and they recognised a more interactive relationship with material possessions,

than the theories suggested. Furthermore, such arguments failed to account for the fact

that consumers use cultural goods for their own ends. For instance, one couple bought a

large Georgian property, not to symbolise their wealth, but to play a part in its

restoration and the preservation of its historic beauty. They saw this as a wonderful

opportunity to indulge in their ‘hobby’ of restoring old houses.

Baudrillard’s (1970) work was an important addition to production-led arguments,

because of his emphasis upon advertising and signification. The younger respondents in my

study felt that magazines were a mechanism for sustaining desires for goods and a major

factor in the creation of the signs and symbols attached to possessions. Their responses

though, highlighted the limitations of production-led arguments for its neglect of the

utility of objects. For all the respondents, both utility and symbolic elements were

combined in the appropriation of most household goods. Many were bought for their

functional uses, but were also chosen for their wider symbolic meaning. Their homes and

contents held associations with both instrumental and symbolic aspects. The nature of this

symbolism is a point to which I now turn.

Goods involve a communication of ideas. This communication process incorporates the

application of symbolic and motivational factors (Lury 1996). Communication occurs

throughout the purchase and display of goods as it relates to common shared meanings

affiliated to particular groups and factions (Bourdieu 1984). According to Dittmar (1992),

the symbolic qualities of goods refer to both shared cultural meanings and personal

values. From my research, communication related more overtly to self-reflection and

personal identification, rather than as a purposeful message to others. They highlighted

these as the motivational factors behind their purchase of goods.

The symbolic meanings attached to their household goods were highly personalised and

individual. During the interviews, each respondent disclosed that they treasured their

homes and contents for its aesthetic beauty and unique qualities. They denied however,

that symbolic attachments related to culturally held beliefs. They seemed to equate this

with status symbols, which they associated with negative images. The only respondents who

openly admitted to buying goods for their culturally shared meaning were the young female

respondents. They were motivated to purchase goods which they believed to be fashionable,

but combined this with other motivational factors, such as use-value, aesthetic quality

and personal associations. The fact that they bought these goods were also as a marker of

their status identity. No shame was associated with gaining pleasure from displaying

tasteful goods that friends would also admire. They hoped these goods would symbolise

their social standing and that this would be reflected through their good taste.

All the respondents with larger properties did not associate their purchasing motives with

a desire to symbolise their status. All saw it as an activity ‘other’ people

were involved in. From the interview transcripts it would not have been overtly apparent

that they lived in such splendid properties. Obviously, when asked to describe their

homes, each documented it physical characteristics, but all the respondents downplayed the

grandness of their homes. None had purchased their home to gain status prestige. This was

contrary to what I had expected from reading Veblen’s (1925), theory about peoples

participation in conspicuous consumption activities. Apart from the young female

respondents, all others adamantly denied that they bought goods to symbolise their status.

This however, does not constitute that their possessions were not equated with culturally

held symbols by others. Each interviewee did recognise the culturally shared meanings

associated with some of their possessions, but they denied this was a motive behind their

purchase. Whilst, I agree that this may be true, I think it may have played a more

subconscious role than they realise. However, to claim that their motives involved

elements of conspicuous consumption would be to translate the meaning of goods onto the

meaning of action. This is the very practice Campbell (1996) criticised other sociologists

for doing. Information obtained was extrapolated from what the respondents themselves said

and from my observations of how they interacted with their homes and possessions. I did

not note whether they owned certain goods and infer meaning from them. A combination of

responses and observations of their interaction with their material environment, helped me

to gain a more representative account. What most respondents hoped their homes constituted

was a warm and welcoming environment, rather than a symbol of wealth. They felt that they

did not need large homes or praise from others, but bought their homes simply because they

loved them and would enjoy living in them.

From my research I found that goods do carry social meanings as Bourdieu (1984) asserted.

He was correct when he claimed that people are neither fully conscious of their motives,

nor passive consumers. Bourdieu (1984) argued that social action, and by this he meant

consumption motives, lies somewhere between these two positions. Whilst their homes and

possessions carried a vast amount of symbolic meaning, whether cultural or personal, the

respondents could not always readily identify with the full extent of their motives. Thus,

the use of observation helped to complete the full picture of the relationship people have

with their homes.

The most important quality that the home signified was the pleasure it gave to them. The

design of the house and its possessions gave them infinite personal satisfaction and

reaffirmed their own sense of self. It is crucial to recognise that possessions do not

have a singular fixed meaning. Peoples’ possessions and the ways they interact with

them constitute different meanings. For instance, a very plain room can represent order

and style to some and scarcity and lack of vibrancy to others.

The younger respondents were more eager to show that they owned what they held to be

desirable property. Even so, they stated they bought it for the lack of work it required

and its suitable location for work. The older respondents all said their purchase had be

motivated by the aesthetic beauty of the property. However, the very character of their

homes were communicating messages, however subconsciously this may have been to them. One

could not have failed to be impressed by this catalogue of impressive, yet varied styles

and design of homes. Respondents spoke of the pleasure their homes gave to them as an

important part of the relationship between them and their possessions. However, homes

cannot escape the wider meanings they communicate to ‘others’. Of all the homes

I visited I was struck by the presentation of them. They were all, what I would term

‘lived in’, but were also very orderly. Even those who thought their homes

looked cluttered, were immaculate. All the respondents were from the middle-class

category, and their homes reflected their ‘relative’ wealth, as all had

necessities and a long list of luxury items. Even the young couples, who were decorating

and furnishing their homes slowly, because of reduced funds, had fairly well furnished

homes. From my observations the homes reflected that they were professional couples, who

enjoyed a range of interests, from house restoration and decoration, to gardening and

pursuits away from the home. The interests of the younger couples aged between 20 to 30

years were reflected within the interior of their homes, whilst those of 30 years and

above showed a greater interest in the exterior style of their properties. Those above 40

years of age demonstrated interest in all areas of their houses. I had not expected such

an affinity with specific areas of the home in accordance with age. Space seemed to be an

important part of the home environment, with certain rooms affecting the way they

conceptualised their homes and identity. This is not to suggest that other areas of the

house are disliked or an incorrect representation of the self and their lifestyles, but

that different areas represent the multiplicity of their tastes and preferences. The

respondents over 55 years saw the home as a inter-linked space, with common themes

throughout. The home constituted an entire place of enjoyment. None of these issues had

been contemplated prior to my research.

All interviewees belonged to the middle classes, but were from different areas within this

category, each with their varied tastes and preferences. This explains why their houses

differed in character and physical structure. The youngest age range were the most similar

in their responses, including their likes and aspirations. Those between 55 and 70 years

displayed almost identical answers between partners and similarities were evident

throughout this age group. Those between 30 and 55 years held similarities, but their

desire towards owning unusual, unique homes was formed in different images. Each wanted to

create a home environment which reflected them, and as Bourdieu (1984) explained,

possessions are as much about marking social differences as they are about striving to

achieve group status measures.

My findings in part relate to Dittmar’s (1992) work. Dittmar saw the meaning of

possessions for identity, as a combination of instrumental and symbolic aspects. By

instrumental, she argues that objects have a use-related function, whether it gives rise

to emotional significance or in some way signifies that experience (Dittmar 1992:89). The

symbolic character embodies two areas; self-expressive aspects, like objects reflecting

personal qualities or signifying relationships and categorical aspects which symbolise

group membership, social position, and status (Dittmar 1992:89). Whilst I agree that

possessions embody these meaning categories, it is not as clear cut as Dittmar suggests.

These meanings are often greatly intertwined and less easily identifiable as distinctive

meanings. One factor that this research could not identify was whether some goods become

personalised because of their categorical associated status. A consumer would be reluctant

to admit this, and possibly unaware that they may consume something partly for its

cultural meaning and then translate this into a meaning affecting ones self-identity.

Thus, by personalising goods, the meaning or initial motivation to purchase may diminish.

This is not to suggest that my respondents were blatantly denying they were involved in

buying goods for their cultural associations, but that whilst they manipulate goods for

their own ends, they are not always fully aware they incorporate this complex web of

consumption motives.

Associations with a past era, having a family heirloom or goods with personal experiences

attached to them were common themes running throughout the responses. The younger

respondents treasured items because they symbolised a particular place, time or

relationship. These associations were attached to goods, from a piece of furniture to

jewellery. Those over 55 years all mentioned their passion for a family heirloom. The

aesthetical quality of the objects seemed to be enhanced through this association. All the

female respondents displayed a special relationship with particular objects for one of

these associations. This theme was also common among the male respondents over 30 years.

Similar points were highlighted by Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton from their

empirical investigation (1981).

The aesthetic value of goods was a reoccurring theme in all of the interviews. People

loved their homes and their possessions for their visual beauty. For the younger

respondents pleasure was tied with the process of daydreaming, in as much as their

pleasure was related to their fantasies about what they would one day possess. This

relates to Campbell’s (1989) theory of ‘dream worlds’. However, my

investigation did not measure if this became a disillusioning experience when they

eventually purchased these goods. However, from the answers from the other age categories,

all seemed to experience immense satisfaction from their homes and contents, a

satisfaction which seemed to escalate with time. So whilst pleasure and fantasy are

involved in modern consumption, this is not disheartening experience.

Only one question was asked in relation to advertising, which explains why this project

has not attempted to investigate its importance to consumption. From the responses to the

question I did ask, most were aware of the importance of advertising in creating and

sustaining images, but all thought their influences were subconscious. What I did discover

was that people manipulated these images for their own ends. They may adopt a certain

colour scheme seen in a magazine, but would furnish the rest of the room differently. Most

incorporated a mixture of styles, and influences and tried to personalise their goods and

furnishings.

The major criticism of those writing about material culture is their assumption that